By Dr. Michael Hughes, Research Associate, McNagny Lab & Dr. Kelly McNagny, Principal Investigator, McNagny Lab

By Dr. Michael Hughes, Research Associate, McNagny Lab & Dr. Kelly McNagny, Principal Investigator, McNagny Lab

Have you ever wondered how your body knows to respond to an infection appropriately? When infected with a virus, why does your body immediately make an anti-viral response, and not an anti-bacterial or an allergic response? Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are a relatively new sub-set of immune cells 1. They are on the front lines of your body’s response to infection and injury, and they play a critical role in helping “decide” how best to respond to invading pathogens and tissue-injury.

As their name suggests, ILCs are cells of the innate immune system. Our innate immune response initiates inflammatory signaling, attracts appropriate first responders to the site of infection, and guides activation of adaptive immune cells, mainly T cells, then, later, B cells, to fight infection. In fact, in many ways ILCs behave like helper T cells, as they play key roles in helping other immune cells perform their effector functions. ILCs are distinct from helper T cells in that they respond immediately to infection and they do not express the functional T cell receptors (TCRs) that give T cells their exquisite specificity 1. Thus, ILCs appear to bridge the gap between the innate and adaptive immune responses.

Lead author, Samuel Shin, MSc Student in Experimental Medicine (CBR Member/McNagny Research Group). Image Credit: Samuel Shin.

Despite their importance in bridging the innate and adaptive immune responses, little is known about how ILCs are made. Current models assert that they develop from bone marrow (BM) stem cells. They are thought to mature in the BM, alongside other blood cell precursors, and then leave the BM to populate tissues and organs throughout the body. Samuel Shin, an MSc student in Dr. Kelly McNagny’s research group, challenges this dogma of ILC development 2. In his paper published in Blood Advances, Sam examined the T cell receptor gene status of type 2 ILCs (ILC2s) – a subset of ILCs with an important role in mucosal immunology and allergic lung disease 3. He aimed to use TCR gene rearrangements as a tracer to delineate the origins of these cells. Strikingly, he found that ILC2s show a high frequency of TCR gene rearrangements which are the key first step of T cell development in the thymus.

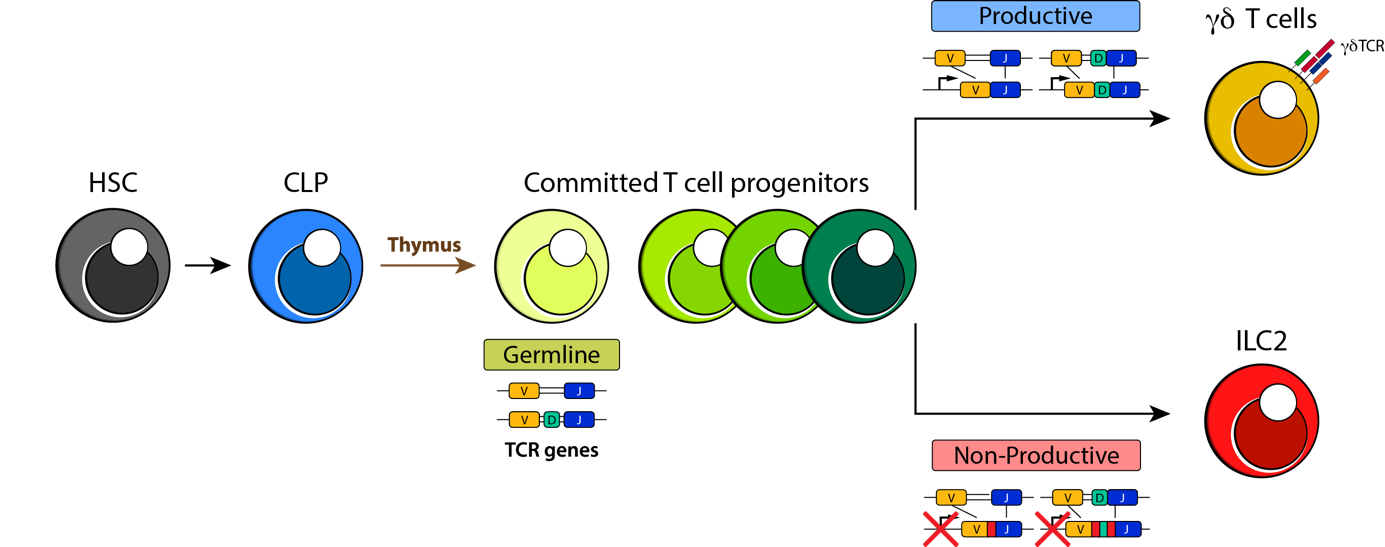

The breakthrough moment was when Sam noticed that ILC2s had tell-tale signs of TCR rearrangement in the gamma (γ) and delta (δ) gene loci (shown in Figure 1). These rearrangements are normally only observed in mature γδ T cells, which are an “unconventional” subset of T cells that traditionally develop in waves around the time of birth. Mature γδ T cells are present in low abundance in tissues compared to classical T cell subsets and they are most prominent in barrier tissues, such as the gut, lungs, and skin. Mature γδ T cells are also unusual in that they respond more broadly to antigens synthesized by groups of pathogens than do conventional T cells. Therefore, like ILC2s, γδ T cells help bridge the innate and adaptive immune responses.

Figure 1. Proposed model of ILC2 development from thymocytes that fail productive γδ T cell receptor rearrangement. Rearrangements in the γ and δ gene loci of lung ILC2s (red) suggest that they are salvaged from immature thymocytes (green) that fail to mature properly into γδ T cells (gold). Image Credit: Samuel Shin, published first as graphical abstract in Blood Advances (2020) 2 and re-printed with permission.

The surprising discovery that ILC2s exhibit signs of gene rearrangement in the γ and δ gene loci suggests that instead of developing in the adult bone marrow, most ILCs mature (likely around the time of birth) in the thymus, which is traditionally thought of as the realm of T cell maturation. Perhaps even more unexpected was the observation that a high frequency of ILCs exhibit out-of-frame gene rearrangements and gene deletions that would preclude their ability to ever express functional TCRs. These previously overlooked rearrangements in the ILC2 TCR genes suggest that ILC2s are salvaged from neonatal thymocytes that fail to mature properly into γδ T cells (proposed model shown in Figure 1). Thus, by carefully tracing TCR gene rearrangements, this work rewrites the life-story of ILC2 development. It suggests that rather than developing in the adult bone marrow, most of these cells develop early in life in the thymus as an offshoot of γδ T cell development. They then colonize developing tissues and from that point forward are largely tissue-resident cells, expanding locally in response to inflammation.

In challenging the dogma of how ILC2s develop, this work hints that other ILC subsets and T cells may also share developmental pathways and may be linked more closely than previously thought. The results of this study provide a framework for developing a better understanding of when and how to isolate and manipulate ILCs for therapies to treat human disease in the future.

References

- E. Vivier et al., Innate Lymphoid Cells: 10 Years On. Cell 174, 1054-1066 (2018).

- S. B. Shin et al., Abortive gammadeltaTCR rearrangements suggest ILC2s are derived from T-cell precursors. Blood Adv 4, 5362-5372 (2020).

- S. Helfrich, B. C. Mindt, J. H. Fritz, C. U. Duerr, Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells in Respiratory Allergic Inflammation. Front Immunol 10, 930 (2019).