By Anthony Hsieh, PhD Candidate at Cote Lab, CBR

By Anthony Hsieh, PhD Candidate at Cote Lab, CBR

The mosquito-borne Zika virus (ZIKV) was first introduced to the Americas in Bahia, a Brazilian state best known for 1000 km of postcard-worthy beaches sporting coconut palms and hot sun. It began in late 2014, when patients with acute exanthematous (skin rash) symptoms began appearing throughout northeast Brazil.1 In March 2015, the origin of this illness was identified as ZIKV in Bahia and northeast Brazilian state Rio Grande do Norte.2,3 Over the past year, the infection has spread to almost all Western hemisphere countries south of and including Mexico.

ZIKV is known in international popular media for its association with microcephaly (abnormally small head), a neurological disorder in newborn babies. In October 2015, increased rates of microcephaly were detected in the state of Pernambuco, Brazil, which appeared to be connected with the Zika outbreak. This prompted an investigation that identified a sweeping surge of microcephaly diagnoses in several Brazilian states compared to previous years. In November, the Brazilian Ministry of Health declared a public health emergency in response to the increased number of microcephaly cases. Since October 2015, 583 cases of microcephaly had been confirmed in Brazil, up from an average of 150-200 per year between 2010 and 2014. In February 2016, the WHO announced a Public Health Emergency of International Concern to address the association between ZIKV and neurologic disorders such as microcephaly.

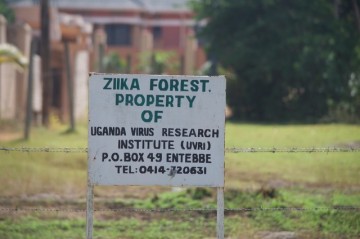

ZIKV was first detected in a rhesus monkey in Zika Forest, Uganda in 1947.4 Since then and prior to its spread to the Americas, circulating virus had been found in tropical regions of Africa, Asia, and the Pacific islands. In fact, a genetic study of the virus indicates that it spread into Brazil via French Polynesia.5 The virus is carried by various mosquito species of the Aedes genus, primarily Aedes aegypti, a species responsible for transmitting viruses closely related to ZIKV such as Dengue, Yellow Fever, and West Nile. Unlike the climate in balmy Bahia and most of the Americas (including the US), the frosty Canadian winter prevents establishment of Aedes aegypti breeding populations.

ZIKV was first detected in a rhesus monkey in Zika Forest, Uganda in 1947.4 Since then and prior to its spread to the Americas, circulating virus had been found in tropical regions of Africa, Asia, and the Pacific islands. In fact, a genetic study of the virus indicates that it spread into Brazil via French Polynesia.5 The virus is carried by various mosquito species of the Aedes genus, primarily Aedes aegypti, a species responsible for transmitting viruses closely related to ZIKV such as Dengue, Yellow Fever, and West Nile. Unlike the climate in balmy Bahia and most of the Americas (including the US), the frosty Canadian winter prevents establishment of Aedes aegypti breeding populations.

Despite the aegis of Canadian frigid air, suspected cases of ZIKV spreading through blood transfusions have been reported in Brazil and French Polynesia6. These cases are difficult to confirm due to both regions being endemic to ZIKV at the time of the report. As a precaution, Canadian Blood Services (CBS) has implemented a 21-day waiting period for blood donors who have travelled outside Canada, the continental United States, or Europe. After 21 days, the virus is cleared from the bloodstream. The Chief Medical and Science Officer of CBS, Dr. Dana Devine, describes the waiting period as “more than adequate”, taking into account suspected cases of infection through blood transfusion in endemic countries. She reminds donors to give blood before they travel.

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) recommends that travellers protect themselves from mosquito bites, and asks pregnant women (or those considering becoming pregnant) to think about postponing travel to ZIKV-affected countries. Travellers returning from affected areas to Canada and the US have brought ZIKV back, with 14 cases of infected Canadian travelers reported as of Feb 25, 2016. However, there have been no reports of local transmission of the virus in Canada. In the US, there are a growing number of cases of suspected sexual transmission, where infections occurred in non-traveller females (including pregnant women) who have had sexual contact with male partners returning from an affected country. Of the 9 pregnant women in the US with ZIKV, 1 infant was born with severe microcephaly.7 Dr. Devine, who is also a principal investigator at the CBR, believes that the current most pressing issue is to establish the true risk of ZIKV to pregnant women. There remains a need to determine whether the link between ZIKV and microcephaly in newborns is associative or causative.

Although ZIKV presents a greater threat against our Southern neighbours, Canadian researchers are prepared to proactively study this virus. Dr. Robbin Lindsay at the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg and Dr. Fiona Hunter at Brock University in Ontario have started investigating whether mosquito species that are able to breed in cold Canadian winters are able to carry and transmit ZIKV. The rising temperatures of the coming seasons may crack the icy shield that has so far prevented the most common ZIKV-transmitting mosquitos from crossing our borders. As for scientists at the CBR, Dr. Devine believes that researchers here have the expertise to determine “whether the technologies that are available to essentially sterilize blood products actually kill Zika virus.” This would not only help in the event that ZIKV-carrying mosquitos invade, but would also contribute to the global fight against this pandemic.